Text excerpted from the book: PROTECTING THE PLANET-Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change (ISBN 978-1-63388-225-6)

by

Budd Titlow & Mariah Tinger

One other notable environmental/social achievement of President Clinton is directly related—by global extension—to the developed nations versus developing nations controversy that is a significant component of today’s Climate Change debate. By Executive Order in 1994, Clinton decreed that “each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission.”

The roots of the Environmental Justice Movement—that Clinton referenced in his decree —can be traced back to Warren County, North Carolina in 1982. With a predominant African-American population, this mostly poor rural county was selected as a site for a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) landfill that handled some of the deadliest carcinogens ever produced by man. More than 500 people were arrested when the community marched in protest.

While their efforts to stop the landfill failed, these demonstrators succeeded in bringing the issue of environmental racism to the forefront of the American public. Their claims emphasized that environmental organizations were run by rich, white people advocating for protection of pristine natural resources while ignoring the conditions of the poor minority populations of the nation.

The prevailing attitude was that natural resources were more important than the ethnic minority populations of the US.

The prevailing attitude was that natural resources were more important than the ethnic minority populations of the US. As a result, many of our nation’s most vile waste products—including radioactive materials—were being deposited in areas predominantly occupied by poor minority homeowners. The driving theory in this disgraceful practice was that there would be less chance of organized opposition since the residents were less likely to be aware of what was happening to their communities.

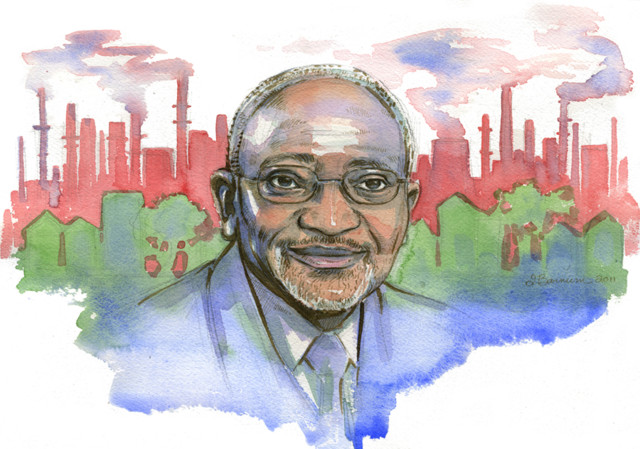

Robert Bullard—Originator / Author

Robert Bullard, often called the “Father of Environmental Justice”, uses his expertise and media savvy to garner attention for communities burdened with environmental hazards. He has dedicated his career to protecting minority and low-income communities from becoming toxic pollution dump sites. Bullard sees environmental justice issues at the heart of everything, in his words, “The right to vote is a basic right, but if you can’t breathe and your health is impaired and you can’t get to the polls, then what does it matter?”

Dr. Robert Bullard is often called the “Father of Environmental Justice Movement”.

Professor Bullard voiced a loud and clear opinion about the disproportionate number of landfills that were cited near predominantly black communities throughout the South, saying “Just because you are poor, just because you live physically on the wrong ‘side of the tracks’ doesn’t mean that you should be dumped on.” His voice was heard and the implementation of the environmental justice movement occurred.

In 1994, President Bill Clinton summoned Dr. Bullard to the White House to witness the signing of an executive order that would require the federal government to consider the environmental impact on low-income communities before implementing policies. Bullard co-wrote a report titled Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty, 1987-2007: Grassroots Struggles to Dismantle Environmental Racism which prompted the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to state, “The EPA is committed to delivering a healthy environment for all Americans and is making significant strides in addressing environmental justice concerns.”

Robert Bullard grew up in Elba, Alabama, a small town that kept him closely acquainted with the civil rights movement, as did his parents, activists for the movement. He earned an undergraduate degree in government from Alabama A&M, a historically black university, and subsequently a Master’s degree in Sociology from Atlanta University. Two years after completing a sociology Ph.D. from Iowa State University, he began a study to document environmental discrimination under the Civil Rights Act. Bullard found that, despite a demographic of only 25% African American in Houston, 100% of the city’s solid waste sites, 75% of the privately owned landfills and 75% of the city-owned incinerators were located in black neighborhoods. Since the city of Houston did not have zoning at this time, he knew that individuals in government orchestrated these sitings. This hooked him into the cause.

Dr. Bullard worked his way through academia, holding research positions and professorships at a number of universities in Texas, Tennessee, California among others. He currently holds a position as Dean of the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs at Texas Southern University in Houston, Texas. As with many of our Climate Change Heroes, Bullard works in academia, but turns his attention and voice to political matters and advocates vociferously for his cause.

Bullard’s book, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality was the first tome on environmental justice issues. Bullard believes that sustainability cannot exist without justice. As he puts it, “This whole question of environment, economics, and equity is a three-legged stool. If the third leg of that stool is dealt with as an afterthought, that stool won’t stand. The equity components have to be given equal weight.” To him, part of the solution is to pair mainstream environmental groups with environmental-justice groups that have the ability to mobilize large numbers of constituents. This type of grassroots movement will get people marching and filling up courtrooms and city council meetings to kick off conversations about environmental movement. He believes that reality will force collaboration and that the awareness that our actions in the developed world have impacts that are not isolated to just us. While this is a step in the right direction, we need to move it to another level of action and policy and apply the framework that environmental justice has laid out to be used across developing countries.

Robert Bullard has received countless awards, including: The Grio’s 100 black history makers in the making, Planet Harmony’s African American Green Hero, and Newsweek’s top Environmental Leaders of the Century. In 2013, he was the first African American to win the Sierra Club John Muir Award, and in 2014 the Club named its new Environmental Justice Award after Dr. Bullard.

Author’s bio:For the past 50 years, professional ecologist and conservationist Budd Titlow has used his pen and camera to capture the awe and wonders of our natural world. His goal has always been to inspire others to both appreciate and enjoy what he sees. Now he has one main question: Can we save humankind’s place — within nature’s beauty — before it’s too late? Budd’s two latest books are dedicated to answering this perplexing dilemma. PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change, a non-fiction book, examines whether we still have the environmental heroes among us — harking back to such past heroes as Audubon, Hemenway, Muir, Douglas, Leopold, Brower, Carson, and Meadows — needed to accomplish this goal. Next, using fact-filled and entertaining story-telling, his latest book — COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across America — provides the answers we all seek and need.Having published five books, more than 500 photo-essays, and 5,000 photographs, Budd Titlow lives with his music educator wife, Debby, in San Diego, California.