by

Budd Titlow

The semantic battle between conservationists and preservationists continued after President Teddy Roosevelt and U.S. Forest Service Supervisor Gifford Pinchot left office. The preservationists believed the conservationists were exposing the nation’s natural resources to widespread overuse and eventual destruction while the conservationists categorized the preservationists as idealistic amateurs—precursors to today’s tree-huggers—who had their heads in the sand when it came to economic reality. The whole situation was really brought to a fever pitch during a rancorous battle over the proposal to dam the Tuolomne River and flood Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park.

Let’s start by looking at the need for putting a water supply reservoir in Yosemite National Park in the first place. You likely know about the historic earthquake that struck the City of San Francisco in 1906. Blamed for more than 3,000 deaths and 80% urban devastation, the “Great Quake” still ranks as one of the worst natural disasters to ever hit the US. But you might not realize that the massive conflagration of fires sparked by the quake showed the woefully poor quality of the city’s water infrastructure. There simply wasn’t enough water anywhere to successfully douse the fires, so they basically roared unabated throughout the entire city.

Ironically, the city fathers had just been dealing with this classically difficult human needs versus natural resource protection issue for two years before the earthquake struck. From the human perspective, Hetch Hetchy Canyon—located 167 miles west of San Francisco—offered the perfect topographic configuration for constructing a dam and reservoir that would provide a long-term solution to San Francisco’s water needs. On the natural side of the ledger, the Hetch Hetchy Valley was rivaled only by the Yosemite Valley in terms of spectacular scenery, abundant wildlife, and marvelously varied recreational opportunities.

As so often happens following a calamity, the severity of the earthquake and fires flipped the ongoing debate in favor of damming the Tuolomne River as it flowed through Hetch Hetchy. So in 1908, the US Department of the Interior—which had previously denied a permit—granted the City of San Francisco’s application for development rights of the Tuolumne River in Hetch Hetchy Canyon. With this decision firmly in hand, the process of planning for construction of the Hetch Hetchy Dam would soon follow … or so the city fathers thought. What they hadn’t planned on was a feisty fellow named John Muir and his legion of devoted followers in a newly formed conservation organization known as The Sierra Club.

Muir used articles in national magazines to rail against the environmental tyranny of the Hetch Hetchy Dam and build widespread opposition to the project. But before we go any further with this part of Muir’s story, let’s take a look at exactly who this man was and why he was so willing to take on such formidable foes as the City of San Francisco and the US Department of the Interior.

John Muir was born in 1838 to a very strict and religious family in Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland. By his own account, Muir spent his boyhood alternating between two seemingly incongruous pursuits—playground fighting and searching for bird’s nests. His love of nature led to regular ramblings around his Scottish coastal plain home and frequent lashings from his father who believed any activities that didn’t involve Bible study were a waste of time. An itinerant Presbyterian minister, Muir’s father often treated him harshly and insisted that he memorize the Bible so that—by age 11—he knew almost the entire text by heart.

In 1849 seeking a stricter religious foundation than he had in Scotland, Muir’s father moved the family to Fountain Lake Farm near Portage, Wisconsin. From the time he hit Wisconsin soil, Muir’s life as an adventurer took off in earnest. While he didn’t connect with his characteristic long, thick beard, tousled hair, piercing grey eyes, and crooked walking stick until adulthood, his tireless ramblings took him all over the Wisconsin countryside through his college days at the State University in Madison.

Afterward graduation, he joined his older brother collecting plants and stomping through swamps in southern Ontario, hiking the Niagara Escarpment, taking a 1,000 mile stroll from Indiana to Cedar Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast, sailing to Havana, Cuba, and then cruising up the Atlantic seaboard to New York City. From New York, Muir booked passage to California and—finally in 1868, at age 30—made his way to the Yosemite Valley, the place that was to become the land of his lasting legacy and unrelenting devotion.

After working as a sheepherder in the California Sierra Nevada—“The Range of Light” as he referred to it—high country for a season, Muir took a job in 1869 building a sawmill in the Yosemite Valley. In his free time, he roamed Yosemite, where he developed a scientific theory that the valley had been carved by glaciers and then unconditionally surrendered to nature. Muir felt a spiritual connection to nature. He believed that mankind is just one part of an interconnected natural world, not its master, and that God is only revealed through nature.

Muir’s love of the western high country gave his writings a special spiritual quality. His readers—including presidents, congressmen, and “just plain folks”—were inspired and often moved to take action by the enthusiasm of his unbounded love of nature.

John Muir relaxing in his beloved Yosemite National Park.

After four years of rejoicing in the Sierra High Country, Muir moved back to the City of Oakland in 1873 where he could more easily earn a living with his writing. He was still espousing the ecstasy he felt traipsing about in the natural world but he was now doing it through articles in leading literary publications like Atlantic Monthly, Overland Monthly,Scribner’s, and Harper’s Magazine. These published articles soon made Muir nationally famous and helped him build strong coalitions throughout the government, corporate, and political worlds. He combined these strong contacts with his widespread national fame and critical acclaim as a speaker, activist, and proposal writer to become our Nation’s most accomplished and important land preservationist.

Muir soon became the public voice for setting aside the high country around the Yosemite Valley as a national park in 1890, thereby setting the stage for the nation’s national park system. Muir was also personally involved in the creation of Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon National Parks. In 1892, as a further testament to his spreading reputation as the nation’s leading conservationist, Muir and a cadre of his devoted followers founded the Sierra Club to “do something for wildness and make the mountains glad.” Of course, the Sierra Club is now one of the leading environmental organizations on the face of the Earth and Muir served as its first president until his death in 1914.

Muir’s greatest cause celebre came during a 1903 three-night excursion to the Yosemite Valley with President Teddy Roosevelt that has been called and written about many times as “the camping trip that changed America” and for very good reasons. First, Muir successfully persuaded Roosevelt to transfer the spectacular Yosemite Valley and the equally magnificent Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias from state park status to a national park. Then their intense and prolonged—both men were characterized by extreme verbosity—campfire chats no doubt sowed the seeds for federal protection of such other iconic western landscapes as: Chaco Canyon, New Mexico; Devils Tower, Wyoming; El Morro, New Mexico; Gila Cliff Dwellings, New Mexico; Grand Canyon, Arizona; Jewel Cave, South Dakota; Montezuma Castle, Arizona; Muir Woods, California; Natural Bridges, Utah; Navajo, Arizona; Pinnacles, California; Tonto, Arizona; Petrified Forest, Arizona; Tumacacori, Arizona, and Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone, California (now Lassen Volcanic National Park).[i]

This trip away from the tightly wound vagaries of Washington, DC and The White House had a profound and lasting impact on national conservation policies throughout the rest of Roosevelt’s presidency. Of his Yosemite escape with Muir, Roosevelt fondly remembered, “It was like lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by the hand of man. There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite, the groves of the giant sequoias and redwoods … our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children’s children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred.”

Now let’s return to the epic battle over Hetch Hetchy which was, by far, the most titanic and traumatic struggle of Muir’s life. In Muir’s tragically touching words: “These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the Mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar. Dam the Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has been consecrated by the heart of man.”

Muir’s battling preservationists also drew withering fire from the citizens of San Francisco who believed they advocated for destruction of their city’s long-term growth. The issue was finally decided in 1913 when Congress passed the Hetch Hetchy Dam Bill by a large margin. John Muir was truly devastated and heartbroken. A pristine jewel of the land that he had spent the best years of his life exploring and writing about was about to be ripped out of its setting and desecrated forever. Many of Muir’s devout followers believed that approval of the Hetch Hetchy Dam cost him his life. After the overwhelming yes vote, Muir became severely stressed and increasingly depressed and died a year later of pneumonia.

On a positive note, Muir’s bountiful life and legacy as America’s first true preservationist has much to offer today’s Climate Change heroes. Often called the “Father of Our National Park System”, Muir lived life to the fullest and—through his writing and speaking—made others aware of the joy he found in his vaunted western cathedrals: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into the trees.”

But Muir also realized the importance of fighting for protection of these iconic landscapes as homage to the entire natural world: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” In the final analysis, he gave his life—battling corporations, city officials, and federal bureaucrats—trying to save a sacred piece of his hallowed cathedral in the High Sierras.

Despite the loss of the battle over Hetch Hetchy, Muir’s legion of preservationists gained quite a bit of traction during the second half of the 20th Century. For one thing they learned that using the print media—magazines and books—could be a very effective tool for rallying public support to their side. Operating in a similar fashion, the Climate Change community should take advantage of every type of media available—particularly now emphasizing Social Media—to espouse the critical importance of maintaining our seashores, coastal wetlands, coral reefs, and oceanic icefields for all future generations of Americans to behold and betroth.

Text excerpted from book: “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change” written by Budd Titlow and Mariah Tinger and published by Prometheus Books.

Photo caption and credit: John Muir relaxing in his beloved Yosemite National Park. Copyright Shutterstock.

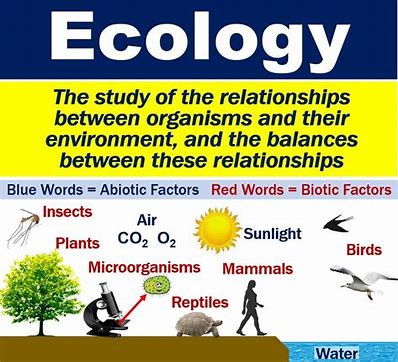

Author’s bio: For the past 50 years, professional ecologist and conservationist Budd Titlow has used his pen and camera to capture the awe and wonders of our natural world. His goal has always been to inspire others to both appreciate and enjoy what he sees. Now he has one main question: Can we save humankind’s place — within nature’s beauty — before it’s too late? Budd’s two latest books are dedicated to answering this perplexing dilemma. “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change”, a non-fiction book, examines whether we still have the environmental heroes among us — harking back to such past heroes as Audubon, Hemenway, Muir, Douglas, Leopold, Brower, Carson, and Meadows — needed to accomplish this goal. Next, using fact-filled and entertaining story-telling, his latest book — “COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across America” — provides the answers we all seek and need. Having published five books, more than 500 photo-essays, and 5,000 photographs, Budd Titlow lives with his music educator wife, Debby, in San Diego, California.