by

Budd Titlow

In 1949, the majority of the US population still—somewhat inexplicably—held fast to the religious fervor that maintained the indomitable belief that the early colonists first brought with them from foreign shores. As we discussed at the very beginning of this section, the dominant thinking was that man had a God-given right to exert dominion over all of nature’s creatures. The general idea was that the beasts of the forests, fields, rivers, and streams were put there to serve man’s needs. Not taking advantage of this natural bounty was still considered a sacrilege and an affront to human integrity almost 175 years after our Nation was founded!

Ironically, the man who was to raise the greatest challenge—to date—to this deeply held belief was an avid outdoorsman himself. As a young adult, Aldo Leopold hunted and fished his native Wisconsin countryside with boundless zeal and aplomb. Then on a hunting trip to Arizona, something happened inside his heart and mind that changed his life forever after he shot a female wolf. But let’s hear the rest of this poignant vignette from the man himself:

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.”

– Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

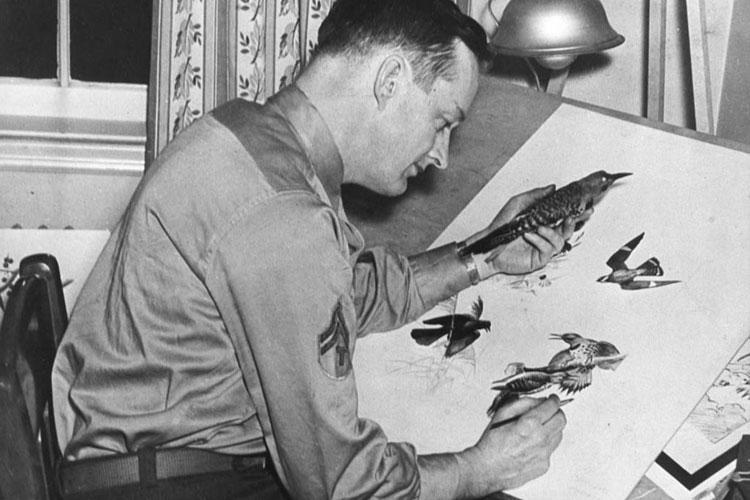

As Aldo Leopold matured from a gung-ho young hunter to a serious researcher of wildlife ecology, he was more often seen with a pair of binoculars around his neck than a rifle slung over his shoulder.

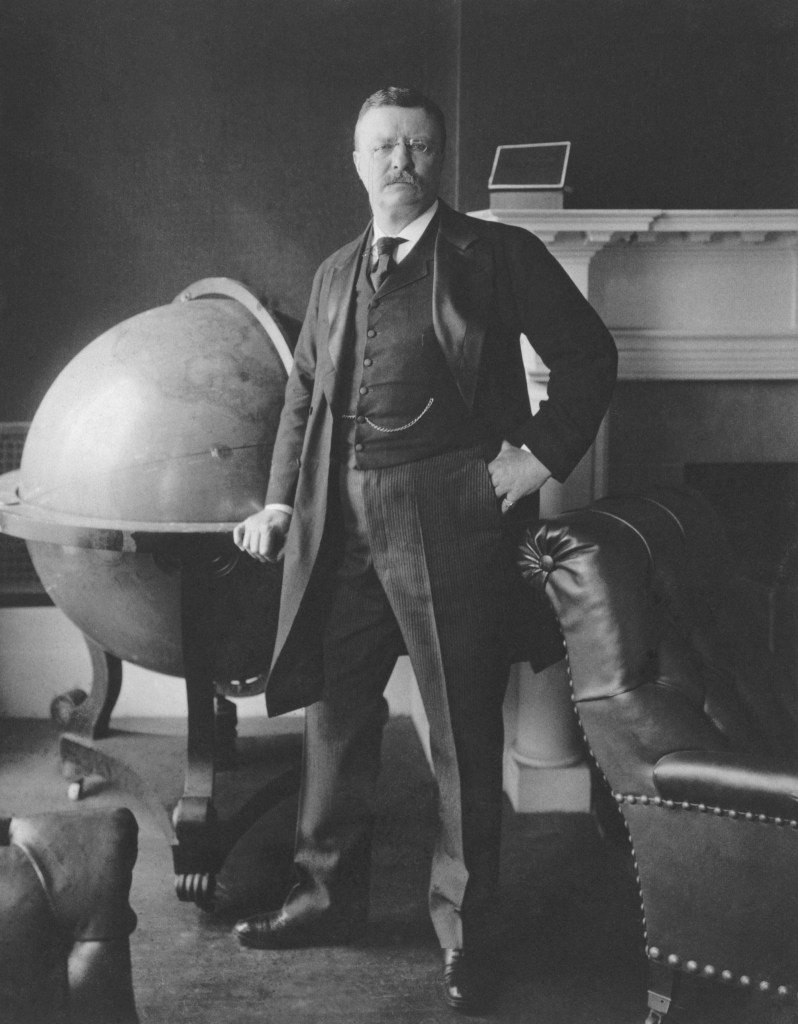

Born in January of 1889 in Burlington, Iowa, Leopold was an outdoorsman almost before he could walk. His dad, a German immigrant and woodcrafter, regularly took the young Aldo on nature forays around the Iowa countryside and—during the summers—in Michigan’s Les Cheneaux Islands in Lake Huron. Attending Yale University, Leopold became one of the first graduates of the Yale school of Forestry which had been created by an endowment from Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief Forester of the US Forest Service.

The experience with the old wolf changed Leopold from a man who took great pleasure in killing animals to one who often relished just watching and documenting what they did. In his younger years—before the “fierce green fire”, he was seldom seen without a hunting jacket on and a high-powered rifle slung over his shoulder. After he shot the wolf—although he didn’t give up hunting—he was more likely to have a long-stem pipe poking thoughtfully out of the corner of his mouth and a pair of binoculars hanging around his neck. Forty years later in 1949, this dramatic change in Leopold’s personal thinking led to the publication of A Sand County Almanac—a book that also changed the thoughts of the entire US Environmental Movement and ushered in a totally new field, the science of wildlife management.

Acknowledged by many as the “Father of Wildlife Conservation” and one of the most influential conservation thinkers of the 20th Century, Leopold was also one of the early leaders of the American wilderness movement. As we have previously discussed—prior to Leopold around the turn of the century—conservation was based almost solely on economics and benefits to humanity.

But in his stirring essay, “The Land Ethic” that concluded A Sand County Almanac, Leopold described his groundbreaking concepts that everything on earth was interrelated and that man and nature existed in a harmonious relationship. These beliefs—which were the precursor to the modern concept of ecology—stressed that man was just part of the overall global ecosystem. Plus—as the most intelligent component of this global ecosystem—man had the responsibility of being the caretaker of all living things on Earth. Leopold also stressed that all living things were owed the right to a healthy existence. These concepts were not only incredibly innovative but also were far ahead of their time.

Leopold wrote A Sand County Almanac from a refurbished chicken coop—which he called simply “The Shack”—located on a farm he was restoring in the sand counties of Wisconsin near Baraboo. With more than two million copies in print and having been translated into 12 languages, this book is one of the most beloved and respected books about the environment ever published.

Ironically, Leopold died in 1948—just a few months before publication of his most famous work—from a heart attack while fighting a forest fire on the property of one of his neighbors. Despite this, his legacy and writings will always live on—both spanning and blending the disciplines of forestry, wildlife management, conservation biology, sustainable agriculture, restoration ecology, private land management, environmental history, literature, education, esthetics, and ethics.

Although Aldo Leopold did not live long enough to hear much—if anything—about Global Warming, his “land ethic” views form the basis of the rationale for combating Climate Change. If he were alive today, he would have most certainly taken a firm stance that as an integral—and supposedly harmonious—part of the natural world, humanity must not only take responsibility for the warming climate, we must also take the lead in combating it. He would emphasize that studying our place within—not outside of—nature will allow us to most effectively see how we are influencing these changes. Then—once we have this understanding—we can go about making the necessary corrections to counteract the looming crisis. As Mike Dombeck, Emeritus Professor of Global Environmental Management at Wisconsin–Stevens Point, recently wrote “As a society, we are just now beginning to realize the depth of Leopold’s work and thinking.”

“Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now, we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free.”

– Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: ‘What good is it?’ To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

– Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

Text excerpted from book: “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change” written by Budd Titlow and Mariah Tinger and published by Prometheus Books. Photo credit: Copyright Shutterstock(2).

Author’s bio: For the past 50 years, professional ecologist and conservationist Budd Titlow has used his pen and camera to capture the awe and wonders of our natural world. His goal has always been to inspire others to both appreciate and enjoy what he sees. Now he has one main question: Can we save humankind’s place — within nature’s beauty — before it’s too late? Budd’s two latest books are dedicated to answering this perplexing dilemma. “PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change”, a non-fiction book, examines whether we still have the environmental heroes among us — harking back to such past heroes as Audubon, Hemenway, Muir, Douglas, Leopold, Brower, Carson, and Meadows — needed to accomplish this goal. Next, using fact-filled and entertaining story-telling, his latest book — “COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across America” — provides the answers we all seek and need. Having published five books, more than 500 photo-essays, and 5,000 photographs, Budd Titlow lives with his music educator wife, Debby, in San Diego, California.