PROLOGUE

Text excerpted from the book: COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across (ISBN: 978-1-80074-568-1)

by

Budd Titlow & Mariah Tinger

There is a lot that our U.S. biology and history books don’t tell us.

Tracking the triumphs and travails of a multi-generational American

family, this book sets the record straight.

From a biological perspective, many American colonists didn’t care

about protecting our native wildlife or conserving our natural resources.

Just think about the once abundant species that are no longer with us —

the passenger pigeon, the eastern elk, the Carolina parakeet, the heath

hen, the American bison (almost), and the black-footed ferret (almost).

Then consider our native tallgrass and midgrass prairies — most of

which were swallowed up by settlers’ plows and then blown away during

the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Finally, look at our air and water quality —

both poisoned by industrialization and still trying to recover.

Sky-filling flocks of now extinct Passenger Pigeons used to be commonplace throughout the U.S.

The Dust Bowl of the 1930’s blew away millions of acres of once-bountiful tall grass prairies.

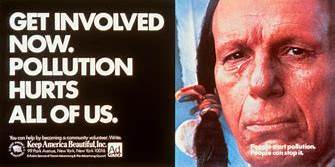

On the history side of the ledger, no group of U.S. citizens has ever

been more disrespected and abused than our Native American tribes.

They respected all species as equals and managed their lands not just in

sustainable ways, but in ways that enhanced the flourishing of the

ecosystem. Yet they lost both their ancestral lands and their cultural

societies to colonial progress.

But — in the end — this book carries a very positive, hopeful

message. We can still extract ourselves from our past faux pas. By

shedding our polarized viewpoints and working cooperatively, we can

still save our planet before it’s too late.

For both of us, this book is a career self-examination. For me (Budd)

the text expresses many things I’ve learned about the natural world

during my fifty years as a wildlife ecologist and resource conservationist.

For me (Mariah), the book’s content captures the joy of the natural world

that my dad (Budd) taught me, how that joy has shaped my career as an

educator and science communicator, and how I hope it influences my

children’s paths. We both see reflections of our past and visions of our

future modeled in the multi-generations of families connected to nature.

Throughout this book, we also emphasize our lifelong beliefs in the

sanctity and equality of all living things — both human and non-human.

Our belief system encompasses all races, religions, cultures, and

lifestyles — but especially those of the Indigenous (or Native) Peoples

of the world.

As expressed in our main title, Coming Full Circle, our book’s

central theme revolves around two primary terms — the circle of life and

biodiversity.

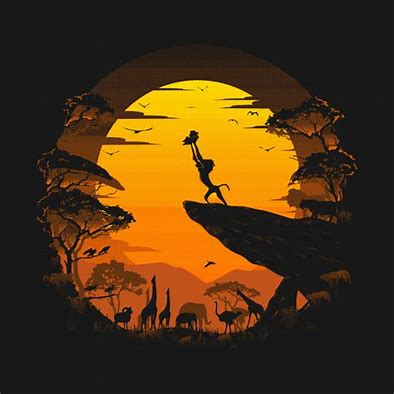

Many of us — especially those with kids or grandkids — know the

first term, the circle of life, as the mega-hit song from the Broadway

musical and blockbuster movie, The Lion King. In reality, the circle of

life is a symbolic representation of birth, survival, and death — which

leads back to birth. For example, an antelope may live for years —

grazing peacefully on African grasslands and producing several healthy

calves. But — as she nears the end of her life and thus her speediness —

a hungry lioness captures and kills her. The antelope dies, but the lioness

brings her body back for the nourishment of her hungry cubs. In this way,

the antelope’s death sustains the life of the lioness’s pride — or family of

lions.

Life is thus represented as a circle because it is a constant loop. The

idea of life as a circle exists across multiple religions and philosophies.

This belief was prevalent throughout the early Indigenous Peoples of

Earth. Unfortunately — owing to what some may term ‘progress’ — this

fervent belief in the circle of life is much less common in today’s world.

The second term — biological diversity, or biodiversity for short —

is primarily used by biologists and ecologists. Biodiversity means the

variety of life — the total number of species, both plants and animals —

living on Earth. This includes everything from the tiniest microbial

spores to the gargantuan blue whale. Generally speaking, the greater the

biodiversity — the total number of species present — the healthier our

planet.

As career environmental scientists, we believe that these two terms

are very closely related. In fact, they build off of and intensify one

another. Picture the diameter of the circle of life as the number of species

that participate in that circle. In our antelope-lioness example above, the

diameter would include the lioness and her pride, the antelope and her

calves, the grass that the antelope eats, the vultures that feed upon the

remainder of the antelope’s carcass, the decomposers that help break

down what the vultures leave behind — and so on. In this manner, the

circle of life is always intricately populated with species and

interdependencies. The larger the circle — in terms of its diameter — the

greater Earth’s biodiversity and vice versa. Because of this, we use these

terms interchangeably throughout this text.

Unfortunately, the circle of life — or biodiversity — of the United

States has decreased dramatically since the first European immigrants

landed on our shores. By telling this fictional account — partially based

on historical facts — of one multi-generational family of American

immigrants, this book explores how and why this change has occurred

and how we will — eventually — come back around to again achieve closure of

the circle of life and — in so doing — save our beautiful planet for all

future generations.

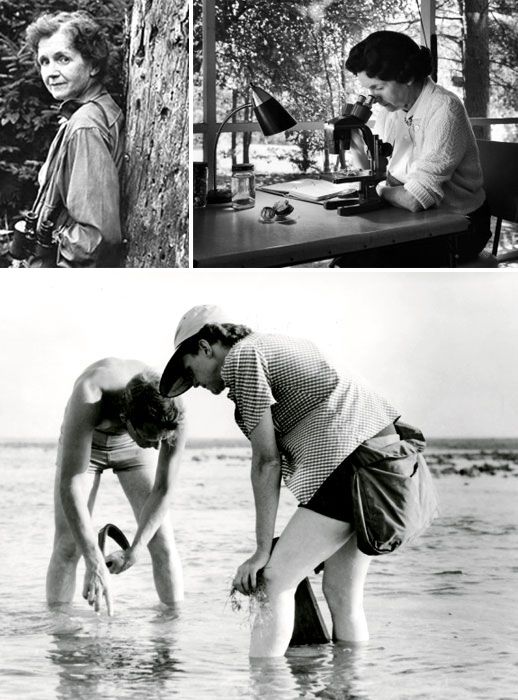

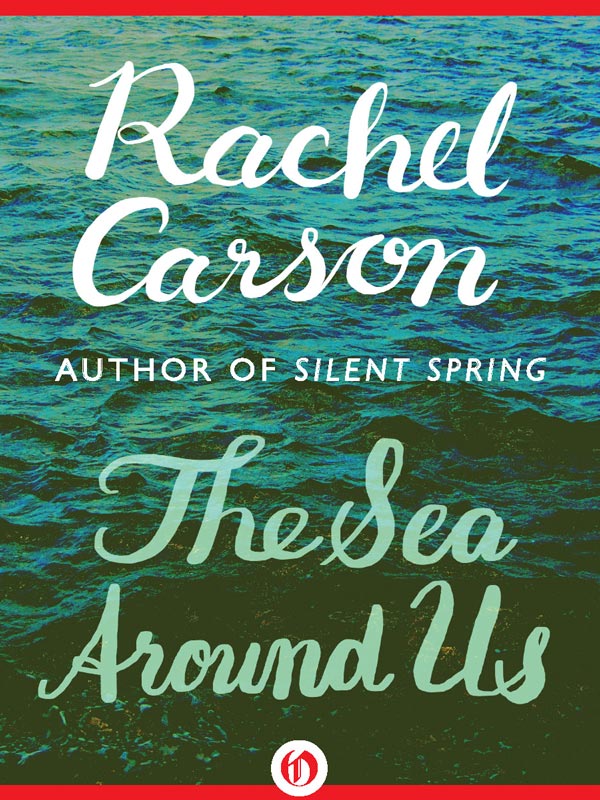

Author’s bio:For the past 50 years, professional ecologist and conservationist Budd Titlow has used his pen and camera to capture the awe and wonders of our natural world. His goal has always been to inspire others to both appreciate and enjoy what he sees. Now he has one main question: Can we save humankind’s place — within nature’s beauty — before it’s too late? Budd’s two latest books are dedicated to answering this perplexing dilemma. PROTECTING THE PLANET: Environmental Champions from Conservation to Climate Change, a non-fiction book, examines whether we still have the environmental heroes among us — harking back to such past heroes as Audubon, Hemenway, Muir, Douglas, Leopold, Brower, Carson, and Meadows — needed to accomplish this goal. Next, using fact-filled and entertaining story-telling, his latest book — COMING FULL CIRCLE: A Sweeping Saga of Conservation Stewardship Across America — provides the answers we all seek and need.Having published five books, more than 500 photo-essays, and 5,000 photographs, Budd Titlow lives with his music educator wife, Debby, in San Diego, California.